- Received June 07, 2021

- Accepted June 23, 2021

- Publication July 26, 2021

- Visibility 7 Views

- Downloads 1 Downloads

- DOI 10.18231/j.ijpi.2021.018

-

CrossMark

- Citation

The influence of gingival biotypes on periodontal health: A cross-sectional study in a tertiary care center

- Author Details:

-

Tony Kurien J *

-

Vivek Narayan

-

Baiju RM

-

Anju P

-

Sneha G Thomas

Introduction

Periodontal health is a complex entity which is influenced by a multitude of modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. These inimical factors can affect the initiation, progression and also the severity of periodontal diseases and conditions.[1] Identification of the detrimental factor(s) and understanding the possible mechanism involved will not only help to target the subjects for disease prevention and treatment, but also in modifying the possible risk factor, and thus forms the pivotal aspects for the control of periodontal diseases. Various studies have documented that the response of periodontium to physical and various treatment measures is dependent on the dimensional characteristics of the tissues.[2], [3]

Gingival biotype is defined as the thickness of gingiva in the labio-lingual direction.[4] Seibert and Lindhe put forward the categorization of thin-scalloped and thick-flat gingival biotype. [5] The latest systematic review of gingival morphology proposed the thin-scalloped, thick flat and thick-scalloped classification.[6] The 2017 World Workshop on the classification of periodontal and peri-implant disease and condition has recommended the adoption of the term periodontal phenotype, based on gingival phenotype and thickness of facial andor buccal bone plate.[7] Nonetheless, by definition, biotype is genetically predetermined and cannot be modified.

Variations in gingival biotype will result in diversity of the clinical manifestations during periodontal disease process. Hence thin gingival biotype might cope with inflammation by apical migration of gingival margin, whereas thick gingival biotype may exhibit deep pocket formation.[8] There are conflicting evidences regarding the association of thin gingival biotype with bleeding on probing. In the study by Muller and Heinecke,[9] it was reported that thin gingival biotype with insufficient keratinized tissue width are not likely to bleed after probing. However, results published by Muller and Kononen [10] showed that sites with thin gingival biotype had higher tendency to bleed. In addition, limited clinical works have been carried out to evaluate the relationship between gingival biotype on plaque accumulation and related changes on periodontium. Hence the present study was conducted to determine the prevalence of different gingival biotype and to analyze its effect on various determinants of periodontal health.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 112 systemically healthy Indian patients above 18 years of age, who reported to the out-patient section of Department of Periodontics, Government Dental College, Kottayam. The inclusion criteria were the presence of all anterior teeth in both maxillary and mandibular arch without any restorations, wasting diseases and malalignment. Subjects who were having mouth breathing habit, taking antibiotics, hormonal replacement therapy or any other medications which could alter the gingival morphology, pregnant or lactation mothers, smokers, history of any type of periodontal treatment six months before, as well as those with the history of and/or on-going orthodontic treatment were excluded. The participants were informed about the purpose of the study, amount of discomfort which might occur and informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the institutional ethical committee (Ref. No. IEC/M/14/2017/DCK dated 15/11/2017).

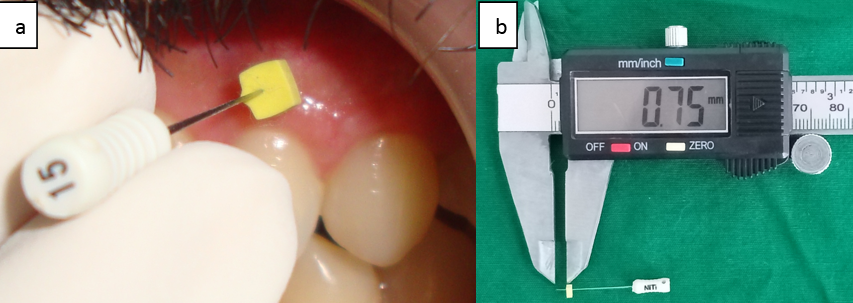

The gingival thickness was measured by one examiner, based on the method described earlier. [11] Briefly, the gingival thickness was assessed mid-buccally in the attached gingiva half-way between the mucogingival junction and marginal gingiva on all the six anterior teeth of both the jaws. After the area was anesthetized using xylocaine spray, a #15 endodontic spreader (Dentsply, India) with a rubber stopper was inserted in a perpendicular direction. The rubber stopper was slided up to the buccal aspect of the gingiva ([Figure 1]a). The distance from the tip of the spreader to the rubber stopper was measured using a digital vernier caliper with a resolution of 0.01mm ([Figure 1]b). From the scores of six teeth, mean gingival thickness of maxillary and mandibular arch separately was calculated. The subjects were classified as having thin gingival biotype (Group I) if the value was <1.5mm and those with measurement ≥2mm as thick gingival biotype (Group II).[12]

A second examiner, who was blinded about the subject’s gingival biotype, recorded the details of the patient on the custom-made proforma to control any bias. Additional data which were recorded to assess oral health condition was the DMFT index, oral hygiene index which is composed of the combined debris Index and calculus Index. [13] Periodontal health stature was evaluated based on; a) modified gingival index [14] b) pocket probing depth, c) gingival recession and d) clinical attachment level. All the computable values were recorded as full mouth measurement. Each tooth was assessed at 4 sites (mesio-buccal, mid-buccal, disto-buccal and lingual/ palatal). From the total scores obtained, the mean score for the entire dentition was calculated.

Statistical analysis

The data collected from the study participants was entered into a spreadsheet (MS Excel) and imported into statistical software (IBM SPSS version 24). While quantitative variables (age, oral hygiene index, DMFT, modified gingival index, pocket probing depth, gingival thickness, gingival recession and clinical attachment level) were summarized using mean and standard deviation, frequencies of categorical variables (gender, gingival biotype) were expressed as proportions. Mann Whitney U tests were used to compare differences of quantitative variables between thin and thick gingival biotype groups. Pearsons correlation tests were used to assess bivariate correlation and separate multiple linear regression models were constructed for modified gingival index score and interproximal attachment loss as outcome variables using backward method. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant for all tests.

Results

The demographic data of study is presented in [Table 1]. In the study, 112 patients (59 males and 53 females) were examined, of which 54 subjects [27 males out of 53 subjects (50.9%) and 27 females out of 45 subjects (60%)] had thin gingival biotype and 44 subjects [26 males out of 53 subjects (49.1%) and 18 females out of 45 subjects (40%)] had thick gingival biotype. The mean gingival thickness observed from the study was 1.49±0.59. From the data obtained, the prevalence of thin gingival biotype was 48.21% and that of thick gingival biotype was 39.28%. Data of fourteen subjects could not be included in the analysis as their mean gingival thickness was between 1.5 and 2mm.

The mean age of patient in Group I and Group II was 40.94±9.34 years and 29.3±8.32 years respectively. Mean gingival thickness in males were 1.54±0.6 and in females it was 1.43±0.59. However, the difference between them were not significant (p>0.05). Mandibular gingival thickness was marginally higher (1.62±1.16) than the maxillary arch gingival thickness (1.56±1.19). Particulars related to oral hygiene practices showed that the majority of subjects (of both the groups) used tooth brush with tooth powder twice daily in horizontal direction (data not presented).

The mean score of all the parameters pertaining to oral health in general and periodontal status in specific were higher in Group I and significant difference was present when compared to thick gingival biotype, ([Table 2]). For better reflection of periodontal disease, interproximal pocket probing depth, interproximal gingival recession and interproximal attachment loss scores were compared between the groups. The results showed that the subjects with thin gingival biotype had greater mean of scores of all the mentioned parameters and was statistically significant using Mann Whitney U-test.

The correlation of clinical variables with gingivitis (based on modified gingival index score) and periodontitis (based on interproximal attachment loss score) was assessed using Pearson coefficient. The results which are presented in [Table 3] show that gingival thickness had a significant negative correlation with modified gingival index and interproximal attachment loss scores. Additionally, oral hygiene index and interproximal gingival recession had a positive correlation with the above-mentioned variables, which was also statistically significant.

Separate multivariable models were constructed using linear regression with modified gingival index and interproximal attachment loss as outcome variables. Out of the four predictor variables in the final model which were statistically significant, gingival thickness had negative correlation with modified gingival index score while oral hygiene index score, pocket probing depth score and gingival recession score showed positive correlation ([Table 4]). The only two independent variables which were found to be statistically significant to predict periodontitis in the final model were gingival thickness and interproximal gingival recession, of which gingival thickness had a negative correlation ([Table 5]).

|

Parameter |

Number of subjects |

Age (in years) Mean±S.D |

Gender distribution of GB |

GT (Mean±S.D) |

||

|

Males |

Females |

Maxilla |

Mandible |

|||

|

(N=98) |

(N=53) |

(N=45) |

||||

|

Group I Thin GB |

54 (55.1%) |

40.94±9.34 |

27 (50.9%) |

27 (60%) |

1.56±1.19 |

1.62±1.16 |

|

Group I Thick GB |

44 (44.89%) |

29.3±8.32 |

26 (49.1%) |

18 (40%) |

||

|

|

|

|

N.S(X2) |

N.S(t) |

|

Variable |

Group I(Mean±S.D) |

Group II(Mean±S.D) |

S.S |

|

DMFT |

2.59±1.96 |

2.02±2.86 |

N.S(t) |

|

OHI |

2.41±0.97 |

1.25±0.55 |

S# |

|

MGI |

1.39±0.73 |

0.53±0.31 |

S# |

|

PPD |

1.70±0.66 |

1.24±0.25 |

S# |

|

GR |

1.21±0.86 |

0.70±0.48 |

S# |

|

CAL |

1.95±1.78 |

0.80±0.45 |

S# |

|

IPD |

1.34±0.48 |

0.68±0.26 |

S# |

|

IGR |

1.20±0.57 |

0.67±0.26 |

S# |

|

ICAL |

1.64±0.68 |

0.79±0.26 |

S# |

|

Variable |

Correlation with MGI score |

S.S |

Correlation with ICAL score |

S.S |

|

GT |

-0.560 |

S¶ |

-0.612 |

S¶ |

|

OHI |

0.468 |

S¶ |

0.374 |

S¶ |

|

IGR |

0.301 |

S¶ |

0.664 |

S¶ |

|

Predictor Variables |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

S.S |

|

GT |

-0.341 |

S‡ |

|

OHI |

0.200 |

S‡ |

|

PPD |

0.302 |

S‡ |

|

GR Score |

0.304 |

S‡ |

|

Predictor Variables |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

S.S |

|

GT |

-0.406 |

S‡ |

|

IGR |

0.591 |

S‡ |

Discussion

Morphology and dimension of gingiva differs from subject to subject and even among different areas of mouth. Determination of gingival thickness can be considered to be an important aspect in relation to periodontal treatment, for restorations at esthetic zone, soft tissue augmentation procedures and in implant dentistry.[3], [15], [16] The present cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate the gingival biotype prevalence and its association with general oral health and periodontal clinical parameters. Among the varied factors that define gingival biotype, the current study selected the mid-buccal thickness of attached gingiva as the site of assessment.

This study, similar to earlier reports, revealed higher prevalence of thick gingival biotype in younger age group, which could be attributable to the presence of adipose tissue, small mucous glands and increased keratinization.[17], [18] The results of the current study show predominance of thicker gingival biotype in male cohorts, which is in concurrence with earlier studies.[19], [20] However, American Academy of Periodontology best-evidence consensus review by Kim et al summarized that gingival biotype is not influenced by age and gender.[7]

Eventhough the observation of the present study point toward the presence of thick gingival biotype in mandible, which is similar to an earlier report, the difference was not significant when compared with maxillary arch.[17] Diverseness exist in literature regarding the distribution of gingival biotype in maxilla and mandible, with Cuny-Houchmand et al report of thick gingival biotype in maxilla, and Pacual et al conclusion that of soft and hard tissue dimensions of anterior teeth in both the arches are commensurable.[21], [22] The former researchers indicated that a difference may exist between the gingival biotype of maxilla and mandible. Recent evidence-based review summarized that there is no major difference between the overall gingival thickness in maxilla and mandible.[7]

The prevalence of thin biotype ranges from 12%-81% has been mentioned in literature, and is dependent on the definition and methods used to assess the biotype.[6] Thin gingival biotype was more prevalent than thick gingival biotype among the total subjects who were examined. Other studies have observed a higher prevalence of thick periodontal biotype.[19], [23] Both the studies adopted a different methodology and grading in assessing gingival biotype. As the grading system used in the present study does not consider gingival thickness between 1.5-2mm, there were omissions of data in the final analysis. However it overcomes the thin cutting edge difference of 1mm to differentiate two gingival biotype variants. Also question remains if the cutoff value of 1mm represents the best threshold for diagnostic purposes.[24]

Comparative analysis between the types of gingival biotype based on the clinical parameters of periodontal health was done. Thin gingival biotype variant was associated with more oral hygiene index score and the related features of periodontal pathology. The etiology and pathogenesis of periodontal disease and subsequent destruction of the tissues can be dependent on gingival biotype.[19] Thicker gingival biotype has a greater dimensional stability owing to the presence of lamina bone adjacent to the outer cortical plate that provides the foundation for metabolic support of cortical bone. Absence or scarce lamina bone in thin biotypes predisposes the cortical bone for faster destruction.[25] In a similar clinical study on patients with mild or moderate plaque induced gingivitis of age between 18-23 years, the authors reported the higher propensity of bleeding on probing in thin gingival biotype situations.[26]

Thick gingival tissue is characterized by flat soft tissue and bony architecture with dense fibrotic connective tissue. It affiliates with a sizeable amount of attached gingiva and hence is mostly resistant to trauma. Kao et al described the nature of response of thick and thin gingival biotype to inflammation. The former type shows the tendency for fibrotic changes and formation of periodontal pocket, while the latter form has a more erythematosus presentation and predilection for tissue recession.[27] This mechanism would explain to a certain extent the identification of higher mean score of modified gingival index score and gingival recession in thin gingival biotype variant in the present study. In contrast to the literature reports, the mean probing depth was higher in the thin gingival biotype group. Different mean pocket probing depth associated with different gingival thickness are in fact an expression of the site specific biologic width.[28] Hence a biologically admissible reasoning to the observed discrepancy regarding pocket probing depth can be possible only with the information of biologic width, which was not documented.

2017 World Workshop on the classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions mentioned that the key to periodontitis case definition is the presence of interdental clinical attachment loss.[29] Hence as a novel investigation, analysis of interdental periodontal health of the two types of gingival biotype was done. Enhanced interdental tissue destruction, based on higher interproximal pocket probing depth, interproximal gingival recession and interproximal attachment loss scores were found in thin gingival biotype subjects. A thin gingival biotype is more prone for interdental tissue destruction as it is associated with a papilla of lesser dimension than that of thick gingival biotype.[30] However, lack of radiographic images impeded additional evaluation of interdental areas. Accordingly, future research should be carried out to substantiate the observed clinical informations.

Correlation analysis of gingival thickness with gingival inflammation and periodontal tissue destruction showed a protective effect of gingival dimension. With a progressive increase of gingival thickness, there was a reduction of gingivitis and periodontitis as evident by the decline of modified gingival index and interproximal attachment loss scores. It can be presumed that the characteristic features of thick gingiva such as large keratinized tissue, flat soft tissue with thick bony plates, location of gingival margin mostly coronal to cementoenamel junction, provides a better anatomical form which is more resistant to affliction.[31] In the linear regression model, gingival thickness has been identified as a significant predictor variable for gingivitis (modified gingival index as the clinical parameter) and periodontitis (interproximal attachment loss score as the clinical parameter) with a negative association for both. Similar negative association was also reported by Müller and Könönen.[26] In a recent cross-sectional study on subjects with reduced periodontium, the researchers observed that the sites with recession had significantly thinner gingival thickness (1.28±0.54mm).[32] Similarly, the current model showing interproximal gingival recession scores as a positive predictor variable upholds the aforementioned relationship.

The results of this cross-sectional study in a tertiary care setting have shown that there are subject and location wise variations in gingival thickness. There is a significant association of gingival biotype with clinical parameters of periodontal pathology. Greater dimensions of gingiva have a seclusive effect on gingival inflammation. The novel attempt to identify the relationship of gingival thickness with periodontitis based on interdental tissue assessment has shown a similar association. However, few limitations to mention with regards to the current investigation are; the lack of assessment of teeth dimensions and non-measurement of bony architecture which could have influenced the gingival morphology. Hence further studies considering the observed limitations and comprising of more number of subjects should be conducted.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this paper.

Source of Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- P E Petersen, P C Baehni. Periodontal health and global public health. Periodontol 2007. [Google Scholar]

- I Joss-Vassalli, C Grebenstein, N Topouzelis, A Sculean, C Katsaros. Orthodontic therapy and gingival recession: a systematic review. Orthod Craniofac Res 2010. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- DS Thoma, N Naenni, E Figuero, CHF Hämmerle, F Schwarz, RE Jung. Effects of soft tissue augmentation procedures on peri-implant health or disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res 2018. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- J C Kois. Predictable single-tooth peri-implant esthetics: Five diagnostic keys. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2004. [Google Scholar]

- J L Seibert, J Lindhe, J Lindhe, Demark: Munksgaard. Esthetics snd periodontal therapy. Textbook of Clinical Periodontology 2nd Edn. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- J Zweers, RZ Thomas, DE Slot, AS Weisgold, FGA Van der Weijden. Characteristics of periodontal biotype, its dimensions, associations and prevalence: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol 2014. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- DM Kim, SH Bassir, TT Nguyen. Effect of gingival phenotype on the maintenance of periodontal health: An American Academy of Periodontology best evidence review. J Periodontol 2020. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- F Liu, G Pelekos, LJ Jin. The gingival biotype in a cohort of Chinese subjects with and without history of periodontal disease. J Periodont Res 2017. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- HP Müller, A Heinecke. The influence of gingival dimensions on bleeding upon probing in young adults with plaque-induced gingivitis. Clin Oral Investig 2002. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- HP Muller, E Kononen. Variance components of gingival thickness. J Periodontal Res 2005. [Google Scholar]

- R Shah, NK Sowmya, DS Mehta. Prevalence of gingival biotype and its relationship to clinical parameters. Contemp Clin Dent 2015. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- N Claffey, D Shanley. Relationship of gingival thickness and bleeding to loss of probing attachment in shallow sites following nonsurgical periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol 1986. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- JC Greene, JR Vermillion. The oral hygiene index: a method for classifying oral hygiene status. J Am Dent Assoc 1960. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- R R Lobene, T Weatherford, N M Ross, R A Lamm, L Menaker. A modified gingival index for use in clinical trials. Clin Prev Dent 1986. [Google Scholar]

- J Tao, Y Wu, J Chen, J Su. A follow-up study of up to 5 years of metal-ceramic crowns in maxillary central incisiors for different gingival biotypes. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent 2014. [Google Scholar]

- F Suárez-López del Amo, GH Lin, A Monje, P Galindo-Moreno, HL Wang. Influence of Soft Tissue Thickness on Peri-Implant Marginal Bone Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Periodontol 2016. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- KL Vandana, B Savitha. Thickness of gingiva in association with age, gender and dental arch location. J Clin Periodontol 2005. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- V Agarwal, Sunny, N Mehrotra, V Vijay. Gingival biotype assessment: Variations in gingival thickness with regard to age, gender, and arch location. Indian J Dent Sci 2017. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- R G Manjunath, A Rana, A Sarkar. Gingival Biotype Assessment in a Healthy Periodontium: Transgingival Probing Method. J Clin Diagn Res 2015. [Google Scholar]

- A Joshi, G Suragimath, S A Zope, S R Ashwinirani, S A Varma. Comparison of gingival biotype between different genders based on measurement of dentopapillary complex. J Clin Diagn Res 2017. [Google Scholar]

- M Cuny-Houchmand, S Renaudin, M Leroul, L Planche, LL Guehennec, A Soueidan. Gingival Biotype Assessement: Visual Inspection Relevance And Maxillary Versus Mandibular Comparison. Open Dent J 2013. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- A Pascual, L Barallat, A Santos, P Levi, M Vicario, J Nart. Comparison of Periodontal Biotypes Between Maxillary and Mandibular Anterior Teeth: A Clinical and Radiographic Study. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent 2017. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- M Olsson, J Lindhe. Periodontal characteristics in individuals with varying form of the upper central incisors. J Clin Periodontol 1991. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- NA Frost, BL Mealey, AA Jones, G Huynh-Ba. Periodontal Biotype: Gingival Thickness as It Relates to Probe Visibility and Buccal Plate Thickness. J Periodontol 2015. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- S Abraham, KT Deepak, R Ambili, C Preeja, V Archana. Gingival biotype and its clinical significance – A review. Saudi J Dent Res 2014. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- HP Muller, D Kononen. Variance components of gingival thickness. J Peridont Res 2003. [Google Scholar]

- R T Kao, M C Fagan, G J Conte. Thick vs. thin gingival biotypes: a key determinant in treatment planning for dental implants. J Calif Dent Assoc 2008. [Google Scholar]

- H-P Muller, T Eger. Masticatory mucosa and periodontal phenotype: A review. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent 2002. [Google Scholar]

- MS Tonetti, H Greenwell, KS Kornman. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Clin Periodontol 2018. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]

- S Abraham, P R Athira. Correlation of gingival tissue biotypes with age, gender and tooth morphology: A cross sectional study using probe transparency method. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Z R Esfahrood, M Kadkhodazadeh, M R Talebi Ardakani. Gingival biotype: a review. Gen Dent 2013. [Google Scholar]

- WZ Lee, MMA Ong, ABK Yeo. Gingival profiles in a select Asian cohort: A pilot study. J Investig Clin Dent 2018. [Google Scholar] [Crossref]